Designing with Nature, Living with Purpose: Key Perspectives on Architecture (and Life) with Ken Yeang

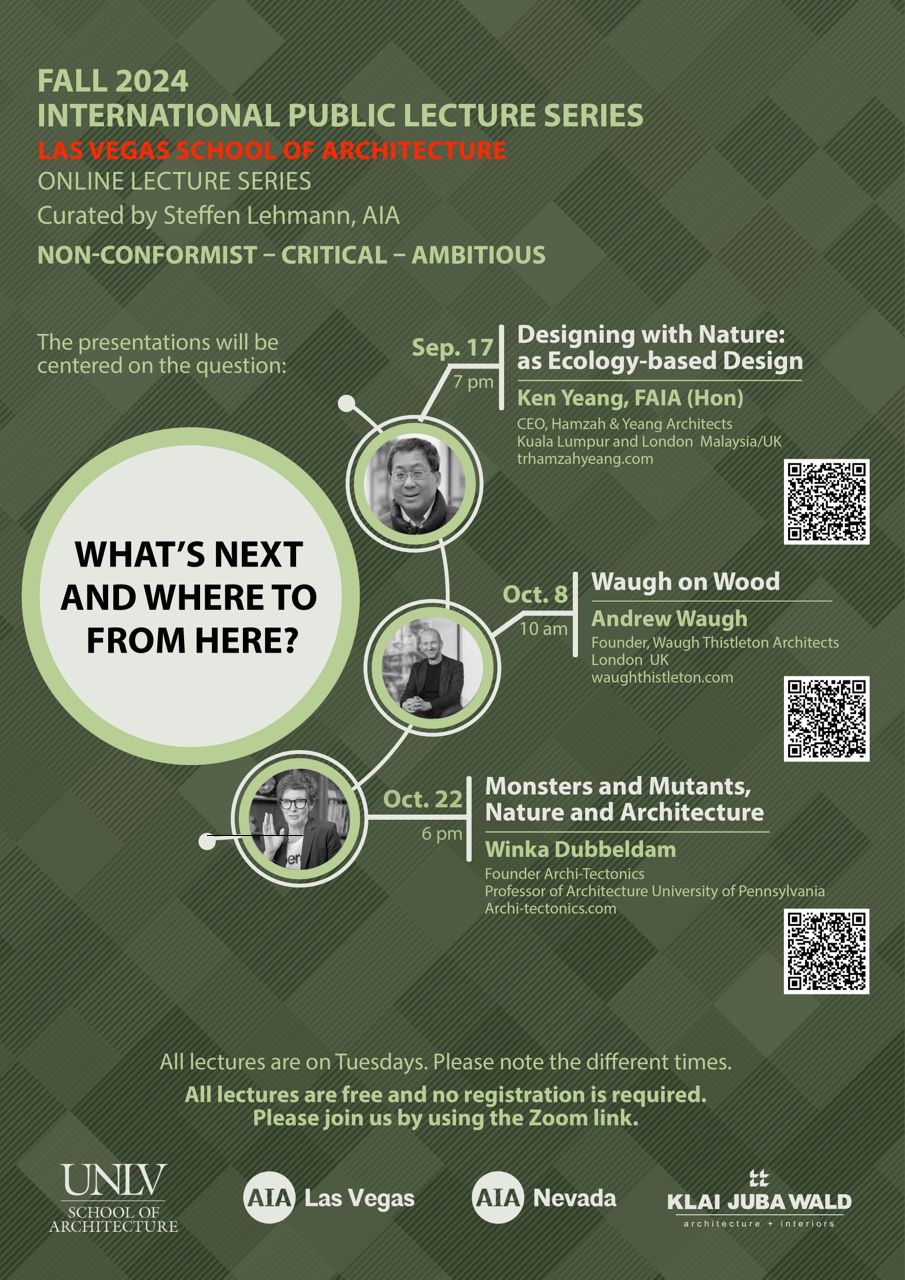

Blog featured on Archidex: Dato’ Dr. Ken Yeang, as the pioneer of ecological design, turned a youthful rebellion into a lifelong mission. From his Cambridge thesis to his globally acclaimed bioclimatic skyscrapers, Yeang has spent five decades redefining green and ecological design.

Read more at https://archidex.com.my/day-2-designing-with-nature-living-with-purpose-key-perspectives-on-architecture-and-life-with-ken-yeang/

Read more at https://archidex.com.my/day-2-designing-with-nature-living-with-purpose-key-perspectives-on-architecture-and-life-with-ken-yeang/

CNN interview (2007)

CNN spoke to Ken Yeang, architect and ecologist about his work to combine architecture and environmental awareness.

CNN: How does being an ecologist relate to being an architect? Ken Yeang: The ecologist has a much more comprehensive and holistic view of the world. We're looking at the natural environment as well as the human built environment and the connectivity between the two -- how do the natural environment and the human-built environment interact and interface with each other. That means when we design a building we're not looking at it as an art object by itself. We're looking at its relationship with the natural environment and how the two interface.

CNN: What's your inspiration behind bringing ecology and architecture together? KY: Biology I suppose. In my heart I believe that biology is the beginning and the end of everything. It's the biggest source of ideas, the biggest source of invention. Nobody can invent better than nature and so if you like nature is my biggest source of inspiration.

CNN: What exactly is eco-design? How are the building designed with these principles different from regular buildings? KY: Eco-design is designing in such a way that the human built environment or our design system integrates benignly and seamlessly with the natural environment. We have to look at it not just as designing a building as an independent object in the city or in the site where it's located. We have to look at it in the context of the characteristics of the site in which it's located, the ecological features and we have to integrate with it physically, systemically and temporally. Physical integration means integrating with the physical characteristics of the place: Its topography, its ground water, its hydrology, its vegetation and the different species on the particular site. Systemic integration is integrating with the processes that take place in nature with our human built environment: The use of water, the use of energy, the use of waste and sewers and so forth. Both the human and the natural must blend together, so there will be no pollution and no waste. Temporal integration, means integrating the rate of our use of the resources in the earth and its material, and the rate of replenishment.

CNN: What are the advantages and approaches of the more holistic approach to building? KY: I think buildings should imitate ecological systems. Ecological systems in nature before we had human beings you know interfere with them exist in a state of stasis -- they are self-supporting, self-sustaining.

Gallery: Exploring Ken Yeang's vision Biography: Ken Yeang Green buildings that touch the sky There are many characteristics in the ecosystem that we could imitate. For instance in most ecological systems you have a composite, biotic components as well as abiotic components acting together to form a whole, whereas in a human built environment most of the components are abiotic or they are inorganic. One of the first things we need to do is to complement the inorganic components with more organic components, and to make them interact to form a whole.

If you look into the way that materials are used in an ecological system you'll notice that you'll find that there is no waste. The waste of one organism becomes food for another and everything's recycled in an ecological system whereas in our human built environment there's a throughput system. We use something then we throw it away. But natural factors don't go away, they have to go somewhere so most times it either ends up in the ground or has to go to a landfill somewhere. We have to imitate nature and try to re-use everything we make as human beings or recycle them -- when we cannot re-use or recycle them we should try to reintegrate them back into the natural environment.

Another process that we should imitate is that in nature the only source of energy is from the sun. So in ecological systems everything comes from the sun through the process of photosynthesis whereas now in human built environment our source of energy is from fossil fuels, renewable, wood energy or hydro-energy but it is not from the sun. So until we are able to operate and run a human built environment by imitating photosynthesis it will be a long while before we can have a true eco-system.

CNN: Can the work you do be used to improve the ecology of current buildings? KY: Yes. We shouldn't just look at new buildings but at existing stock building because that's an even greater problem than the new buildings being built. The renovation of existing buildings and making them green is just as important as designing new green buildings.

CNN: What would you do to an existing building to make it greener? KY: I think some of the ways we could make these buildings environmentally friendly, is just common sense. Better use of space, improving the insulation, getting more daylight into the buildings, reducing the energy consumption of the air conditioning and heating systems, making sure that the internal air quality is good, that we have increased natural ventilation opportunities in the mid seasons. You know these are some of the things we can do.

CNN: Can you tell us a little bit about the EDITT tower in Singapore? KY: EDITT Tower is a project where we wanted to exemplify all our ideas in one single building. I should add it is a tower and towers are the most unecological of all building types. Generally a tower uses 30% more energy and materials to build and to operate than anther structure, but towers, as a built form, will be with us for a while, until we find an economically viable alternative. My contention is that if we have to build these towers then we should make them as humane and as ecological as possible. It's a dirty job but somebody has to do it. In the EDITT tower we tried to balance the inorganic mass of the tower with more organic mass, which means bringing vegetation and landscaping into the building. But we didn't want to put all the landscaping in one location. We wanted to spread that over the building, integrate it with the inorganic mass and that we wanted to have it ecologically connected. So we've put the vegetation from the ground all the way up the building and that whenever the building.

Then we wanted it to be low energy, so we had photo voltaics in its façade particularly facing the east and west side and on its roof so it would have its own energy source. We also wanted to collect water so that we could be independent from the water supply. We put water collection on the roof, but because the tower has a very small roof area we had sunshades which were scallop shaped so we could collect rainwater through them as well. So in many ways it feels like a human made ecosystem in a tower form.

CNN: Do you think cities around the world are ready for this new kind of building? Are may ee seeing a move towards better sustainable buildings? KY: I think planners are aware of this. They've been aware for years but they have not been able to implement it because their bosses don't let them implement it. So for instance sustainable urban drainage system is extremely important but a lot of communities they don't practice it. Low energy design is extremely important and that low transportation, you know reduced use of cars and better use of public transportation affects the planning of cities. And so planners all over the world are aware of it, but some are in a better position to implement it that others.

CNN: How important is it for the future that we introduce and implement new kind of architecture? KY: Absolutely important. 100% important, that's something that all designers in the world have to address today otherwise this millennium will be our last.

CNN: Are you optimistic about the future? What are your hopes and dreams? KY: Well I'm eternally optimistic about the future. I believe that you know if we are committed towards it and if we continue to educate people and get the whole world community to implement green features and aspects in not just the built environment not just in their lifestyles but in their businesses in their industries then we're heading towards a green future. So it is a green dream for the future, and as Kermit the frog says it's not easy being green, but we should try to make it as green as possible.

CNN: Do you think by 2020 we are likely to see buildings of this type in our skyline? KY: We'll see green buildings long before 2020 -- I think the movement is intensifying. Within the next 5-10 years we'll see a lot more green buildings being built. Not just buildings but green cities, green environment, green master plans, green products, green lifestyles, green transportation. I'm very optimistic.

CNN: How important are these buildings to the future of the world in regards to climate change? KY: I think green buildings are extremely important but it's only part of the equation. A lot of people think that if I put a green building everything is going to be fine, but actually it's not just the green buildings we need, but green businesses, green governments, green economics. We have to extend the greening of buildings to our business and our lifestyles -- that is the most important thing to do next.

CNN: How does being an ecologist relate to being an architect? Ken Yeang: The ecologist has a much more comprehensive and holistic view of the world. We're looking at the natural environment as well as the human built environment and the connectivity between the two -- how do the natural environment and the human-built environment interact and interface with each other. That means when we design a building we're not looking at it as an art object by itself. We're looking at its relationship with the natural environment and how the two interface.

CNN: What's your inspiration behind bringing ecology and architecture together? KY: Biology I suppose. In my heart I believe that biology is the beginning and the end of everything. It's the biggest source of ideas, the biggest source of invention. Nobody can invent better than nature and so if you like nature is my biggest source of inspiration.

CNN: What exactly is eco-design? How are the building designed with these principles different from regular buildings? KY: Eco-design is designing in such a way that the human built environment or our design system integrates benignly and seamlessly with the natural environment. We have to look at it not just as designing a building as an independent object in the city or in the site where it's located. We have to look at it in the context of the characteristics of the site in which it's located, the ecological features and we have to integrate with it physically, systemically and temporally. Physical integration means integrating with the physical characteristics of the place: Its topography, its ground water, its hydrology, its vegetation and the different species on the particular site. Systemic integration is integrating with the processes that take place in nature with our human built environment: The use of water, the use of energy, the use of waste and sewers and so forth. Both the human and the natural must blend together, so there will be no pollution and no waste. Temporal integration, means integrating the rate of our use of the resources in the earth and its material, and the rate of replenishment.

CNN: What are the advantages and approaches of the more holistic approach to building? KY: I think buildings should imitate ecological systems. Ecological systems in nature before we had human beings you know interfere with them exist in a state of stasis -- they are self-supporting, self-sustaining.

Gallery: Exploring Ken Yeang's vision Biography: Ken Yeang Green buildings that touch the sky There are many characteristics in the ecosystem that we could imitate. For instance in most ecological systems you have a composite, biotic components as well as abiotic components acting together to form a whole, whereas in a human built environment most of the components are abiotic or they are inorganic. One of the first things we need to do is to complement the inorganic components with more organic components, and to make them interact to form a whole.

If you look into the way that materials are used in an ecological system you'll notice that you'll find that there is no waste. The waste of one organism becomes food for another and everything's recycled in an ecological system whereas in our human built environment there's a throughput system. We use something then we throw it away. But natural factors don't go away, they have to go somewhere so most times it either ends up in the ground or has to go to a landfill somewhere. We have to imitate nature and try to re-use everything we make as human beings or recycle them -- when we cannot re-use or recycle them we should try to reintegrate them back into the natural environment.

Another process that we should imitate is that in nature the only source of energy is from the sun. So in ecological systems everything comes from the sun through the process of photosynthesis whereas now in human built environment our source of energy is from fossil fuels, renewable, wood energy or hydro-energy but it is not from the sun. So until we are able to operate and run a human built environment by imitating photosynthesis it will be a long while before we can have a true eco-system.

CNN: Can the work you do be used to improve the ecology of current buildings? KY: Yes. We shouldn't just look at new buildings but at existing stock building because that's an even greater problem than the new buildings being built. The renovation of existing buildings and making them green is just as important as designing new green buildings.

CNN: What would you do to an existing building to make it greener? KY: I think some of the ways we could make these buildings environmentally friendly, is just common sense. Better use of space, improving the insulation, getting more daylight into the buildings, reducing the energy consumption of the air conditioning and heating systems, making sure that the internal air quality is good, that we have increased natural ventilation opportunities in the mid seasons. You know these are some of the things we can do.

CNN: Can you tell us a little bit about the EDITT tower in Singapore? KY: EDITT Tower is a project where we wanted to exemplify all our ideas in one single building. I should add it is a tower and towers are the most unecological of all building types. Generally a tower uses 30% more energy and materials to build and to operate than anther structure, but towers, as a built form, will be with us for a while, until we find an economically viable alternative. My contention is that if we have to build these towers then we should make them as humane and as ecological as possible. It's a dirty job but somebody has to do it. In the EDITT tower we tried to balance the inorganic mass of the tower with more organic mass, which means bringing vegetation and landscaping into the building. But we didn't want to put all the landscaping in one location. We wanted to spread that over the building, integrate it with the inorganic mass and that we wanted to have it ecologically connected. So we've put the vegetation from the ground all the way up the building and that whenever the building.

Then we wanted it to be low energy, so we had photo voltaics in its façade particularly facing the east and west side and on its roof so it would have its own energy source. We also wanted to collect water so that we could be independent from the water supply. We put water collection on the roof, but because the tower has a very small roof area we had sunshades which were scallop shaped so we could collect rainwater through them as well. So in many ways it feels like a human made ecosystem in a tower form.

CNN: Do you think cities around the world are ready for this new kind of building? Are may ee seeing a move towards better sustainable buildings? KY: I think planners are aware of this. They've been aware for years but they have not been able to implement it because their bosses don't let them implement it. So for instance sustainable urban drainage system is extremely important but a lot of communities they don't practice it. Low energy design is extremely important and that low transportation, you know reduced use of cars and better use of public transportation affects the planning of cities. And so planners all over the world are aware of it, but some are in a better position to implement it that others.

CNN: How important is it for the future that we introduce and implement new kind of architecture? KY: Absolutely important. 100% important, that's something that all designers in the world have to address today otherwise this millennium will be our last.

CNN: Are you optimistic about the future? What are your hopes and dreams? KY: Well I'm eternally optimistic about the future. I believe that you know if we are committed towards it and if we continue to educate people and get the whole world community to implement green features and aspects in not just the built environment not just in their lifestyles but in their businesses in their industries then we're heading towards a green future. So it is a green dream for the future, and as Kermit the frog says it's not easy being green, but we should try to make it as green as possible.

CNN: Do you think by 2020 we are likely to see buildings of this type in our skyline? KY: We'll see green buildings long before 2020 -- I think the movement is intensifying. Within the next 5-10 years we'll see a lot more green buildings being built. Not just buildings but green cities, green environment, green master plans, green products, green lifestyles, green transportation. I'm very optimistic.

CNN: How important are these buildings to the future of the world in regards to climate change? KY: I think green buildings are extremely important but it's only part of the equation. A lot of people think that if I put a green building everything is going to be fine, but actually it's not just the green buildings we need, but green businesses, green governments, green economics. We have to extend the greening of buildings to our business and our lifestyles -- that is the most important thing to do next.

Episode 13 - Pioneering Ecology Based Architecture with Ken Yeang

In this episode, Sustainable Futures sits down with architect and visionary Ken Yeang to discuss the the practice of ecological design and how it can and must be used to enhance global resilience and combat climate change.

Read more at https://livingarchitecturemonitor.com/sustainable-futures-podcast/episode-13-pioneering-ecology-based-architecture-with-ken-yeang

Read more at https://livingarchitecturemonitor.com/sustainable-futures-podcast/episode-13-pioneering-ecology-based-architecture-with-ken-yeang

57 Most Famous Architects Of The 21st Century

Yeang is an early pioneer of ecology-based green design and master planning, carrying out design and research in this field since 1971. The Guardian names him as “one of the 50 people who could save the planet”. Yeang’s operating headquarters, Hamzah and Yeang, is in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, with other offices in London and Beijing, China.

Read more at https://www.archute.com/famous-architects-21st-century/

Read more at https://www.archute.com/famous-architects-21st-century/

The Norman Foster Foundation (NFF) presents the ‘On Climate Crisis’ Masterclass Series;

The Norman Foster Foundation (NFF) presents the ‘On Climate Crisis’ Masterclass Series, a collection of video presentations delivered by ten outstanding experts in the fields of architecture, urbanism, landscape architecture, urban law, politics, and environmental science. This initiative aims to support the NFF’s extensive educational programme by fostering an exchange of knowledge and promoting a global conversation on the current climate crisis.

Click here for more

Click here for more

Congratulations to Green Building Pioneer

By: IEN Consultants

Date: Sep 3

https://www.ien.com.my/post/congratulations-to-green-building-pioneer

Date: Sep 3

https://www.ien.com.my/post/congratulations-to-green-building-pioneer

To save the planet, we need to change the way we build

When Malaysian architect Kenneth Yeang began working in the 1970s, the skyscraper was seen as a closed air-conditioned box. Yeang helped reimagine that model with elements like natural ventilation and lighting, sky terraces, and vegetation, as part of what he calls ‘bioclimatic' skyscrapers.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Outcome of the 2024 UIA International Forum in Kuala Lumpur

The International Union of Architects (UIA) is pleased to announce the successful conclusion of the UIA International Forum 2024, held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on 15 to 17 November under the auspices of the Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia (PAM). The event, themed “Diversecity”, explored the profound meaning of diversity in urban contexts, focusing on cultural, social, and environmental inclusivity in city design.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

The Bioclimatic Skyscraper: Kenneth Yeang's Eco-Design Strategies

Rising over global cities, the modern skyscraper has long been a symbol of economic growth and environmental decline. For years, they have been reviled by environmentalists for being uncontrolled energy consumers. Malaysian architect Kenneth Yeang acknowledged the skyscraper as a necessity in modern cities and adopted a pragmatic approach to greening the otherwise unsustainable building typology. Yeang’s bioclimatic skyscrapers blend the economics of space with sustainability and improved living standards.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

4 amazing buildings by Malaysian pioneer of sustainable architecture

This week, our prominent Malaysian architects series proudly features Datuk Dr Ken Yeang, globally known as one of the founding fathers of sustainable architecture.

Years before sustainability became the catchword, Yeang pioneered the concept of bioclimatic skyscrapers, integrating natural ventilation, daylighting, solar shading and vegetation in high-rise design.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

From Mind To Matter: Dato’ Dr Ar Ken Yeang

It’s not every day you get the opportunity to meet someone whose work has contributed and impacted not only the global architectural industry but also Mother Earth itself. And for someone who is nearing his 70s, Dato’ Dr Ar Ken Yeang is presently still very much engrossed in his endeavour to employ biophilic principles in his work.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Why Dr Ken Yeang will not stop toiling for the development of eco-architecture

Despite close to 50 years of hard work, Dr Ken Yeang will stop at nothing to save the planet through the advancement of ecological architecture. Most people would consider 71 a ripe age for retirement. But Dr Ken Yeang is far from taking a back seat at the architectural firm he established with his partner..

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Shape Your Future with Ken Yeang, Eco-architect and visionary

Named by the Guardian newspaper as “One of 50 people who could save the planet”, Dr. Ken Yeang is one of the founding figures in sustainable architecture. Describing himself as an “Ecologist first, architect second”, Dr. Yeang is behind many of the design principles architects use today when creating ecologically sustainable buildings.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Designworks : On innovative ecomimicry

This article first appeared in City & Country, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 12, 2022 - December 18, 2022

Best known for his green architecture and master plans, architect and ecologist Datuk Ken Yeang has been working on green designs since the 1970s and authored more than 12 books on the subject.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

CNBC Transcript: Ken Yeang, Principal Architect, T.R. Hamzah & Yeang

Christine Tan: Ken, as an architect, you first went green in the 1970s. Have you always wanted to be an eco-architect? When was the turning point for you?

Ken Yeang: Well, I originally was appointed as a research worker to work on the “autonomous house” project. The autonomous house project was an idea mooted by American engineer, Buckminster Fuller, for a house that was not connected to the city’s utilities.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

5 Malaysian Architects Delivering Inspiring Architectural Design

Often we talk about the joy of property and the amazing developments we see around us, but what about the people behind these stunning buildings?

Architectural design sometimes seems like a kind of magic from the outside. But modern architecture is about taking an inspiring vision, and using the skills and tools gained over decades of experience to nurture it to life.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Greening the City

In 1984, American biologist Edward O Wilson published his book Biophilia, in which he argued that humans have an innate bond with other living systems. Since then, researchers have found that a connection to nature can lower blood pressure, reduce stress, improve attentiveness, boost creativity and make us generally happier people. And yet the past two centuries of urbanisation have nearly severed our ties with nature, eliminating it from our lives in the worst cases and at best reducing it to decoration – a flower pot on the windowsill, a garden weeded, pruned and rid of pests.

Read more at: Click here

Read more at: Click here

Dr. Ken Yeang Interview with RIBA Journal

‘Hindsight’: interview with Pamela Buxton

Ken Yeang : “blazing a trail for ecological design”

Read here

Ken Yeang : “blazing a trail for ecological design”

Read here

Malaysia's Extraordinary House

In Collaboration with:

DATO' DR. AR. KEN YEANG

T. R. HAMZAH & YEANG

Norman Foster Foundation 2024, Article by Ken Yeang

Our architecture, besides fulfilling their design functions, can be

regarded as life-size experiments in our endeavours to seek solutions

that address the current environmental crisis. The work is nature-based

and founded on the science of ecology. Why ecology? The reason being

the future viability of life for all species (including humans) on the planet

is linked to sustaining the resilient ecological health of the planet.

Read More: Click here

Read More: Click here

The Merdeka Award - Dato' Dr Ken Yeang

Dato' Yeang received his first qualifications in architecture from the Architectural Association School ('AA') in London. His work on the green agenda started in the 1970s with his doctoral dissertation at the University of Cambridge on ecological design and planning.

Adopting an ecology based approach, he successfully applied those principles to architecture and urban design, a pursuit that spanned over nearly 4 decades of his professional life and delivered over 200 built projects. His contribution to architectural design is also acknowledged internationally through numerous awards for his built work.

Cont..

Adopting an ecology based approach, he successfully applied those principles to architecture and urban design, a pursuit that spanned over nearly 4 decades of his professional life and delivered over 200 built projects. His contribution to architectural design is also acknowledged internationally through numerous awards for his built work.

Cont..

Crisis in Climate, Crisis in Design - Ken Yeang

Dr. Yeang began his work on ecological design as a student; his doctoral dissertation “A Theoretical Framework for Incorporating Ecological Considerations in the Design and Planning of the Built Environment” (1975) became the basis for his eventual practice. Understanding that architecture and ecology had yet to be merged, he developed a set of design principles centered around the idea that a building should operate in cohesion with its biosphere. Today, his work is differentiated by an ecosystem-based approach that performs beyond conventional green-rating systems.

Click here to listen: https://currystonefoundation.org/podcast/123-designs-race-rescue-mission/

Click here to listen: https://currystonefoundation.org/podcast/123-designs-race-rescue-mission/

Shape Your Future with Ken Yeang - Full Interview

Shape Your Future” is an editorial series focusing on the 1.000 solutions that are saving our planet. We feature: scientists, pioneers, creatives, humanitarians and more. Aired: 12.30pm (EST) or 6.30pm (CEST).

Ecoarchitecture and Ecomasterplanning: The Work of Ken Yeang - January 2018

Lecture by Ken Yeang. Yeang will discuss an approach to green and sustainable design based on the science of ecology. He will show how ecology and the ecosystem influence the design and planning of the built environment while offering a theoretical descriptive (non-stochastic) model for ecological design. Yeang’s work will illustrate the ideas and principles that he presents.

Read full article here: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/event/ken-yeang-ecoarchitecture-and-ecomasteplanning-the-work-of-ken-yeang/

Read full article here: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/event/ken-yeang-ecoarchitecture-and-ecomasteplanning-the-work-of-ken-yeang/

Episode 13 - Pioneering Ecology Based Architecture with Ken Yeang

In this episode, Sustainable Futures sits down with architect and visionary Ken Yeang to discuss the the practice of ecological design and how it can and must be used to enhance global resilience and combat climate change. Ken has been a pioneer of ecological design and hyper-green architectural design practice, believing in the imperative to design with nature from the ground up. Join us for a conversation on the power of natural systems, the growth of ecological design, and hear about many of the stunning and verdant projects Ken has had a hand in over the course of his illustrious career.

Click here to listen

Click here to listen

Top 10 Most Extraordinary Homes | House Transformation

A journey through the extraordinary, the avant-garde, and the downright mind-blowing. Sharing ideas & inspirations for interior design & architecture. Get ready for a visual feast as we present the top 10 most extraordinary homes in Malaysia.

Interview by Pamela Buxtion (in RiBAJ 2022)

Interview of Ken Yeang by Pamela Buxton in “Hindsight (RIBAJ 25 March 2022).: “Ken Yeang talks about his five-decade-long career, creating his own experimental passive house in 1985 and how it was only in the early 2000’s that clients started asking him for green buildings”.

Q1. Knowing what you know now, did you make the right decision to be an architect?

A2. Most definitely. As an architect now for nearly 50 years, I have enjoyed most moments despite the ups and downs of the economy where the life of as architect can be one of feast and famine. But if I was reincarnated, I don’t think I’d want to come back and go through all the palaver again. If I knew as much as I do now about green design, I would have wasted less time on trivial aspects and would have done everything much better and greener.

Q2.,What sparked your interest in architecture?

A2. In my teens at Cheltenham College I had a keen interest in art and spent a great deal of time painting. Architecture seemed an obvious subject to study at university.

I was also greatly influenced by my uncles, who at that time, in the 1960s, were developers in London. Two of them had studied architecture at Regent Street Polytechnic.

Q3. How important was your time in the UK to your development as an architect?

A3. After Cheltenham College, I trained at the Architectural Association and did a doctorate at Cambridge. I was only 17 when I went to the AA and was the youngest in my year. I really enjoyed it and found that I could do it reasonably well. Those who influenced me greatly at that time were my first-year master, Elia Zenghelis, who was a Modernist through and through, and my 5th year master Peter Cook. I was also greatly influenced by Charles Jencks, who became a close friend.

When I worked one summer at Louis de Soisson Partnership on the Brighton Marina, my immediate boss was Eva Jiricna. Overseeing us was Nathan Silver. I did some illustrations for his book on ‘Adhocism’, which he wrote with Charles Jencks.

During my time there, the English sense of humour became second nature. At that time it was Kenneth Horne, Steptoe & Son, the Carry On series and others, though its hilarious subtleties were difficult to explain to others elsewhere such as the USA or the Far East.

Q4. When did you realise you were drawn towards ecological design?

A4. If you went to the AA Members’ room and stayed long enough you’d meet just about everyone in the architectural world. One night I was introduced to John Frazer, who was doing research on the ‘autonomous house project’, an idea first mooted by Buckminster Fuller. He asked me if I’d work on the project there and then, and I agreed. However, six months into the project I realised that what we were doing was essentially engineering without adequate engineering support from industry (back then in 1972). I felt that the bigger picture of ecological design need to be first addressed. So I obtained leave to be a research student to do a doctorate on ecological design and planning, and attended lectures on ecology at Cambridge’s Department of Environmental Biology. After my doctorate, ecological design and its sub-set bioclimatic design became my life’s agenda. The research habits also stuck, and our practice today is very much research-driven. But It was not until the early 2000s, that I started having clients asking for green buildings. It took 30 years! Architecture is really an old man’s game. Our current work is on developing various experimental built systems in ecological architecture and infrastructures.

Q5. You’ve been in practice for nearly 50 years. Has it been a good time to be an architect?

A5. The business of architecture is totally susceptible to the ups and downs of economic cycles, with the troughs occurring every nine years or so. It can be a struggle during times of recession. Like any business, Pareto Principle (of the 19th-century economist Vilfredo Pareto) applies indicating that the top 20 per cent get the bulk of the business and live reasonably well while the other 80 per cent are scrambling over the remainder. But only the top 2 per cent gets the cream and can become reasonably wealthy, and often through progressive acquisition of properties during the boom times. I do okay, but now I want to move up to that 2 per cent.

Q6. What was your breakthrough project?

A6. My first was an experimental passive-mode, low-energy house in Kuala Lumpur that espouses bioclimatic principles, and which has a number of climate-responsive experiments in it. It was completed in 1985 and became a benchmark for a lot of our other bioclimatic projects. It’s actually my own house where I still live – I call it the Roof-Roof House. I subsequently advanced the bioclimatic principles to the high-rise built form in the Menara Mesiniaga tower, completed in 1991 near Kuala Lumpur. The principles of mixed-mode low-energy design were later applied to a building in the temperate climatic zone, the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital Extension in London, where we incorporated an energy-saving glass flue-wall device in the facade.

Q7. What project are you most proud of?

A7.,We regard ‘our latest as our greatest’. One of our recently completed buildings is the Suasana in Putrajaya, Malaysia, which has a faceted façade like a jewel. We used glass-panels with fritted patterns as a double skin instead of the conventional horizontal sunshades, where the building consumes 30 per cent less energy than a comparative similar building. We also created ‘constructed habitats’ within the builtform to enrich the local biodiversity. Right now I’m at the design stage on a mixed-use complex near India. Here, we’re planning a broad swathe of green eco-infrastructure that traverses across the mid-level of the entire building podium in a nexus with the ecology of the site.

Q8. What has given you the most satisfaction in your work as an architect?

A8. Besides being hyper green, I regard the purpose of architecture is to engender happiness and pleasure to the lives of the people who use or visit our buildings. Achieving this in some of our projects and having it affirmed to us afterwards by the users is probably the most gratifying aspect of my work. It simply justifies the raison d’etre of why I am an architect in the first instance.

Q9. What has been the biggest obstacle to overcome?

A9. When we first started in the mid-1970s, it was extremely difficult to get clients to accept a green architecture. The only way was to design buildings that were climate-responsive (bioclimatic) as passive-mode, low-energy structures that could be armatures for later addition of ecological features. We also designed mixed-mode buildings with partial MEP systems as low-energy buildings. By the time clients started asking for green buildings, we had better engineering support from industry (in the late 90’s). Our early believers and supporters included Battle & McCarthy, and friends such as Paul Hyett, Paul Finch and Dr James Fisher.

Q10. Have your priorities in practice changed over the years??

A10. No. Ecological design has been consistently our primary focus and design agenda. We believe there are four sets of ecological infrastructures that need to be bio-integrated into a designed system: nature (the ecosystems and the biogeochemical cycles); human society (its socio-economic-political-institutional systems); the built environment (artefacts and technologies) and hydrology (water management and regimes). We need to synergistically bring all these systems together into a whole builtform.

Q11. Is it easier, or harder, to get high-quality projects built now than when you started out?

A11. It has become more complex and onerous, as there are numerous other aspects such as achieving near net zero energy and carbon, near net zero wastes, and maximising positive ecological impacts, etc. As Kermit the frog sang in Sesami Street, ‘it’s not easy being green’.

Q12. What do you think has been the secret of your practice’s success?

A12. I am not sure, but I believe there are three factors. The first is that I greatly believe in ‘focus’ in that we cannot be too many things for too many people. The second is that having business acumen is absolutely vital. We are never taught how to run a practice as a business at architectural school, and so in the early years of my practice, in the 1970s, I took night classes in business management. This does not guarantee success, but it provides a systematic basis for operating a practice as a business. Today the application of what I learnt is different in the digital world, but the principles remain the same. The third factor is in developing effective human relationships, not just externally to the business but internally within the company.

Q13.,Looking back on your work over the years, who have been your biggest influences?

A23. There are a few: Professor Ian McHarg, the landscape architect and planner who invented the ecological land use planning technique; the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead who advanced the philosophy of the organism; and Ludwig von Bertalanffy, a systems scientist who developed the general systems theory.

Q14. Is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

A14: If I were to live my professional life again, I’d do an MBA before starting practice as this would give me an edge on others already in the field who did business intuitively. It was not until the early 2000s that I attended a short course at Harvard Business School. It was only a week’s course, but it radically changed my thinking about practice and my outlook on the world.

Q15. Do you think the profession has taken too long to get to grips with the need to design sustainably?

A15. It is not the profession per se that is at fault but the way architects have been taught – schools are taking too long to adapt their curriculums. It is crucially vital that architects learn ecology so that they become conversant with the processes of the natural environment’s systems that take place in the ecosystems and in the planet’s bio-geochemical cycles. Ecology needs to be taught at all schools of architecture; it affects all building site planning, the choice of built and energy systems, the selection of materials and handling of waste, water conservation and hydrology etc. ‘Architects’ Declare’ is a very good movement and is expanding internationally. But human social, economic and political systems need to change radically if we are to live more sustainably.

Q16. Do you have a dream project you’d still like to achieve?

A16. No specific project, but before I start pushing up daisies, my dream is to achieve as much as I can in my ecological agenda of ecomimesis (the emulating, replicating and augmenting of ecosystem attributes) to remake our built environment into constructed (human-made) ecosystems. I’m also interested in cybernetic building – applying smart systems to ecological design.

Q17. What is your most treasured possession?

A17. Life itself is my most treasured possession; to be able to live, to discover, to invent and to advance the field of ecological design for the benefit of humanity, and of all the species and their environments in the planet.

Q1. Knowing what you know now, did you make the right decision to be an architect?

A2. Most definitely. As an architect now for nearly 50 years, I have enjoyed most moments despite the ups and downs of the economy where the life of as architect can be one of feast and famine. But if I was reincarnated, I don’t think I’d want to come back and go through all the palaver again. If I knew as much as I do now about green design, I would have wasted less time on trivial aspects and would have done everything much better and greener.

Q2.,What sparked your interest in architecture?

A2. In my teens at Cheltenham College I had a keen interest in art and spent a great deal of time painting. Architecture seemed an obvious subject to study at university.

I was also greatly influenced by my uncles, who at that time, in the 1960s, were developers in London. Two of them had studied architecture at Regent Street Polytechnic.

Q3. How important was your time in the UK to your development as an architect?

A3. After Cheltenham College, I trained at the Architectural Association and did a doctorate at Cambridge. I was only 17 when I went to the AA and was the youngest in my year. I really enjoyed it and found that I could do it reasonably well. Those who influenced me greatly at that time were my first-year master, Elia Zenghelis, who was a Modernist through and through, and my 5th year master Peter Cook. I was also greatly influenced by Charles Jencks, who became a close friend.

When I worked one summer at Louis de Soisson Partnership on the Brighton Marina, my immediate boss was Eva Jiricna. Overseeing us was Nathan Silver. I did some illustrations for his book on ‘Adhocism’, which he wrote with Charles Jencks.

During my time there, the English sense of humour became second nature. At that time it was Kenneth Horne, Steptoe & Son, the Carry On series and others, though its hilarious subtleties were difficult to explain to others elsewhere such as the USA or the Far East.

Q4. When did you realise you were drawn towards ecological design?

A4. If you went to the AA Members’ room and stayed long enough you’d meet just about everyone in the architectural world. One night I was introduced to John Frazer, who was doing research on the ‘autonomous house project’, an idea first mooted by Buckminster Fuller. He asked me if I’d work on the project there and then, and I agreed. However, six months into the project I realised that what we were doing was essentially engineering without adequate engineering support from industry (back then in 1972). I felt that the bigger picture of ecological design need to be first addressed. So I obtained leave to be a research student to do a doctorate on ecological design and planning, and attended lectures on ecology at Cambridge’s Department of Environmental Biology. After my doctorate, ecological design and its sub-set bioclimatic design became my life’s agenda. The research habits also stuck, and our practice today is very much research-driven. But It was not until the early 2000s, that I started having clients asking for green buildings. It took 30 years! Architecture is really an old man’s game. Our current work is on developing various experimental built systems in ecological architecture and infrastructures.

Q5. You’ve been in practice for nearly 50 years. Has it been a good time to be an architect?

A5. The business of architecture is totally susceptible to the ups and downs of economic cycles, with the troughs occurring every nine years or so. It can be a struggle during times of recession. Like any business, Pareto Principle (of the 19th-century economist Vilfredo Pareto) applies indicating that the top 20 per cent get the bulk of the business and live reasonably well while the other 80 per cent are scrambling over the remainder. But only the top 2 per cent gets the cream and can become reasonably wealthy, and often through progressive acquisition of properties during the boom times. I do okay, but now I want to move up to that 2 per cent.

Q6. What was your breakthrough project?

A6. My first was an experimental passive-mode, low-energy house in Kuala Lumpur that espouses bioclimatic principles, and which has a number of climate-responsive experiments in it. It was completed in 1985 and became a benchmark for a lot of our other bioclimatic projects. It’s actually my own house where I still live – I call it the Roof-Roof House. I subsequently advanced the bioclimatic principles to the high-rise built form in the Menara Mesiniaga tower, completed in 1991 near Kuala Lumpur. The principles of mixed-mode low-energy design were later applied to a building in the temperate climatic zone, the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital Extension in London, where we incorporated an energy-saving glass flue-wall device in the facade.

Q7. What project are you most proud of?

A7.,We regard ‘our latest as our greatest’. One of our recently completed buildings is the Suasana in Putrajaya, Malaysia, which has a faceted façade like a jewel. We used glass-panels with fritted patterns as a double skin instead of the conventional horizontal sunshades, where the building consumes 30 per cent less energy than a comparative similar building. We also created ‘constructed habitats’ within the builtform to enrich the local biodiversity. Right now I’m at the design stage on a mixed-use complex near India. Here, we’re planning a broad swathe of green eco-infrastructure that traverses across the mid-level of the entire building podium in a nexus with the ecology of the site.

Q8. What has given you the most satisfaction in your work as an architect?

A8. Besides being hyper green, I regard the purpose of architecture is to engender happiness and pleasure to the lives of the people who use or visit our buildings. Achieving this in some of our projects and having it affirmed to us afterwards by the users is probably the most gratifying aspect of my work. It simply justifies the raison d’etre of why I am an architect in the first instance.

Q9. What has been the biggest obstacle to overcome?

A9. When we first started in the mid-1970s, it was extremely difficult to get clients to accept a green architecture. The only way was to design buildings that were climate-responsive (bioclimatic) as passive-mode, low-energy structures that could be armatures for later addition of ecological features. We also designed mixed-mode buildings with partial MEP systems as low-energy buildings. By the time clients started asking for green buildings, we had better engineering support from industry (in the late 90’s). Our early believers and supporters included Battle & McCarthy, and friends such as Paul Hyett, Paul Finch and Dr James Fisher.

Q10. Have your priorities in practice changed over the years??

A10. No. Ecological design has been consistently our primary focus and design agenda. We believe there are four sets of ecological infrastructures that need to be bio-integrated into a designed system: nature (the ecosystems and the biogeochemical cycles); human society (its socio-economic-political-institutional systems); the built environment (artefacts and technologies) and hydrology (water management and regimes). We need to synergistically bring all these systems together into a whole builtform.

Q11. Is it easier, or harder, to get high-quality projects built now than when you started out?

A11. It has become more complex and onerous, as there are numerous other aspects such as achieving near net zero energy and carbon, near net zero wastes, and maximising positive ecological impacts, etc. As Kermit the frog sang in Sesami Street, ‘it’s not easy being green’.

Q12. What do you think has been the secret of your practice’s success?

A12. I am not sure, but I believe there are three factors. The first is that I greatly believe in ‘focus’ in that we cannot be too many things for too many people. The second is that having business acumen is absolutely vital. We are never taught how to run a practice as a business at architectural school, and so in the early years of my practice, in the 1970s, I took night classes in business management. This does not guarantee success, but it provides a systematic basis for operating a practice as a business. Today the application of what I learnt is different in the digital world, but the principles remain the same. The third factor is in developing effective human relationships, not just externally to the business but internally within the company.

Q13.,Looking back on your work over the years, who have been your biggest influences?

A23. There are a few: Professor Ian McHarg, the landscape architect and planner who invented the ecological land use planning technique; the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead who advanced the philosophy of the organism; and Ludwig von Bertalanffy, a systems scientist who developed the general systems theory.

Q14. Is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

A14: If I were to live my professional life again, I’d do an MBA before starting practice as this would give me an edge on others already in the field who did business intuitively. It was not until the early 2000s that I attended a short course at Harvard Business School. It was only a week’s course, but it radically changed my thinking about practice and my outlook on the world.

Q15. Do you think the profession has taken too long to get to grips with the need to design sustainably?

A15. It is not the profession per se that is at fault but the way architects have been taught – schools are taking too long to adapt their curriculums. It is crucially vital that architects learn ecology so that they become conversant with the processes of the natural environment’s systems that take place in the ecosystems and in the planet’s bio-geochemical cycles. Ecology needs to be taught at all schools of architecture; it affects all building site planning, the choice of built and energy systems, the selection of materials and handling of waste, water conservation and hydrology etc. ‘Architects’ Declare’ is a very good movement and is expanding internationally. But human social, economic and political systems need to change radically if we are to live more sustainably.

Q16. Do you have a dream project you’d still like to achieve?

A16. No specific project, but before I start pushing up daisies, my dream is to achieve as much as I can in my ecological agenda of ecomimesis (the emulating, replicating and augmenting of ecosystem attributes) to remake our built environment into constructed (human-made) ecosystems. I’m also interested in cybernetic building – applying smart systems to ecological design.

Q17. What is your most treasured possession?

A17. Life itself is my most treasured possession; to be able to live, to discover, to invent and to advance the field of ecological design for the benefit of humanity, and of all the species and their environments in the planet.

Ecoarchitecture and Ecomasterplanning: The Work of Ken Yeang

Yeang discussed an approach to green and sustainable design based on the science of ecology.

The UK Guardian newspaper named him as one of 50 individuals who could save the planet (2008).

Saving the World by Ecological Design | DR. KEN YEANG | TEDxNitteDU

“Everything in nature is connected”

The UK Guardian newspaper named him as one of the 50 individuals who could save the planet (2008)

(Sep 19, 2018)

Shape Your Future with Ken Yeang - Full Interview

“Shape Your Future” is an editorial series focusing on the 1.000 solutions that are saving our planet.

(Sep 23, 2019)

A Green Building Should Look Green, Which Means Hairy!

The well known architect, ecologist and planner reinvented the high-rise typology as "vertical green urbanism" and is known for his authentic ecology-based work and bioclimatic skyscrapers. Filmed in mid February, 2015, Linda Velazquez met with Ken Yeang at his London offices and greatly enjoyed his intellect, ecological aesthetic, world philosophy, and sharp wit.

(May 11, 2016)

An interview with architect Ken Yeang, on CNN's 'Just Imagin

Ken describes his vision for the future of buildings - and how we might live in and organise our cities in 2020, to make them greener.

(Dec 18, 2007)

Rendezvous with architect Ken Yeang

A brief talk with Malaysian revolutionary architect Ken Yeang on his invention of eco-architecture.

(Dec 27, 2018)

Ken Yeang on Designing for a Resilient Planet | 'On Climate Crisis' Masterclass Series

Yeang classifies ecological design into five infrastructures and explores the idea of remaking our built environment as human-made ecosystems, highlighting the need for behavioural changes in our communities to seamlessly integrate within natural systems.

(Jul 27, 2023)

Ecotopia: A Masterclass with Dr. Ken Yeang

Dr. Ken Yeang is an architect, ecologist, planner and author from Malaysia, best known for his ecological architecture and ecomasterplans that have a distinctive green aesthetic. He pioneered an ecology-based architecture, working on the theory and practice of sustainable design.

(Jun 4, 2021)

Ken Yeang - Ecoarchitecture: Projects, Theory, Ideas, Subsystems

Ken Yeang studied at the AA and received his doctorate from Cambridge University. He is principal of Hamzah & Yeang (Malaysia) with offices in the UK (Ken Yeang Design International/Llewelyn Davies Ken Yeang Ltd) and in China (North China Architectural and Engineering Company). In 2008 The Guardian listed Yeang amongst their ‘50 people who could save the planet’, describing him as the ‘world’s leading green skyscraper architect’. Yeang is the architect of several major buildings in Asia including the IBM Building (Malaysia), Solaris (Singapore), the Genome Research Building (Hong Kong), and in the UK, the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital Extension. He is the author of more than a dozen books on architecture.

(Oct 9, 2015)

SUTD Master of Architecture Guest Lecture by Dr. Dr. Ken Yeang

SUTD Master of Architecture Guest Lecture by Dr. Dr. Ken Yeang

(Aug 31, 2022)

Ken Yeang – Designing the Regenerative City

Yeang’s unique ‘ecologically responsible’ architecture is can be seen in Singapore, China, Malaysia, and elsewhere. Now you can hear more about it in this live studio session. Ken will join us live, so be prepared to put your questions to him as the conversation unfolds.

(Nov 24, 2017)

In Person Dato' Dr Kenneth Yeang

Dato' Dr Kenneth Yeang is the 2011 Merdeka Award Recipient, in the Environment category, for outstanding contribution to the development of design methods for the ecological design and planning of the built environment.

(Sep 12, 2012)

What’s a project by another group or individual that you think is pushing the boundaries of sustainable design?

Ken Yeang, HON, FAIA, is one of my architecture heroes.

His biophilic design, Eco-architecture, and ethos in practice are inspiring.

Yeang’s work has a firm basis in the science of ecology and an understanding of culture and place.